Increasing demand for electricity to power AI and data centers

Lessons From the Surfside Condo Collapse

What we don’t know about climate change can hurt us

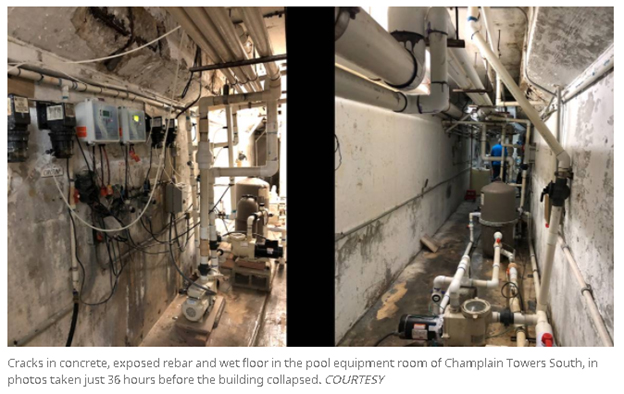

Images from the Miami Herald

The dramatic collapse of the Champlain Tower in Surfside, Florida along the coast north of Miami Beach led to questions about the possible contributing role of climate change. Understanding why it happened is a pressing question, not only because of the more than 140 persons missing or dead attributable to the collapse but because of hundreds of similar buildings that line the coast housing tens of thousands of people. Multiple factors may have been involved including subsidence and saltwater flooding the basement garage, and initial reports are that a full explanation may take years to complete. Yet there are already some significant implications for climate change policy:

1. Warnings of disasters likely to occur often go unheeded until too late. A best selling novel, Condominium, described the collapse of a Florida coastal condominium not unlike that in Surfside — and was published in 1977. In 2016, the real estate firm Zillow predicted that one out of eight homes in Florida would be underwater by 2100. A February 2019 article in The Guardian described the resistance among Florida real estate buyers to the inevitability of sea level rise: “Humans tend to respond to immediate threats and financial consequences — and coastal real estate, especially in Florida, may be on the cusp of delivering that harsh wake-up call.” In 2017 an NPR report on the Miami real estate market noted investors in coastal condominiums expressed little if any concern about climate change.

2. Climate change is a threat multiplier and a likely source of increased risk, even if not the sole or primary factor in any specific disaster. A professor of architecture notes, climate change “can take a very harsh situation — it’s very harsh to live on the ocean — and compound those risks to lead to something like this.” Ocean flooding was known to occur frequently in the building garage. Sea level rise also means saltwater intrusion in groundwater, another potential source of corrosion. More specifically, “Concrete is a porous substance, which makes it possible for salt water to seep inside. When that happens, salt can corrode the steel rebar used to reinforce concrete structures.”

3. The impacts of climate change may only be understood after they occur. The climate system is extraordinarily complex and continues to generate new challenges for science. The impact of rising seas and saltwater on building foundations may be the subject of analysis for years. Similarly, some time will be required before scientists agree on how changes in ocean temperatures and circulation patterns contributed to the “heat dome” that sent temperatures soaring in the Pacific Northwest but also may have been responsible for the Polar Vortex that caused freezing temperatures and power outages in Texas.

4. The human impact may be much greater than the economic costs. In 2018, the Nobel Prize in economics was awarded to William Nordhaus for modeling the costs and benefits of climate change policies, an analysis popular with conservatives because it favors only very gradual policy measures. Note: his assumptions and methodology have been widely criticized). From a macroeconomic perspective, natural disasters can even be a net positive. As a Federal Reserve official observed in the aftermath of Hurricane Andrew, “Perversely, yet fortunately, good economic news often follows disasters,” referring to the influx of insurance and public funds that led to a surge in construction and retail spending. But such thinking neglects the enormous human costs — the impact of growing numbers of deaths and destruction of communities, in other parts of the world a source of mass migration and social conflict. The longer-term economic impacts of disaster- and climate-related displacement are difficult to quantify and remain largely hidden.

5. Delaying investment in resilience measures is a natural human tendency, even when the costs of the consequences are vastly greater. It’s a natural human tendency to downplay abstract risks until they occur. This behavior is even worse when problems are non-linear: “People are much better with obvious threats like that nasty dog at the door than they are with threats that escalate quickly and nonlinearly.” Detailed analysis has shown that $1 spent to meet requirements of disaster-resistant building codes avoids $11 in subsequent costs. The Surfside Condo Board was unable to agree on an assessment to cover $15 million in repairs identified several years ago.

6. Financial risk takers like insurers and mortgage lenders are not substitutes for effective regulation. In recent years, there have been efforts to make the financial sector more aware of climate risk, and more transparent regarding disclosure of such risks for investors. However, in the news coverage of the Surfside collapse there has so far been little reference to the potential responsibility of any financial actor. The insurance industry may be most vulnerable to sudden unexpected increases in risk, although as policies are typically issued annually companies may seek to adjust premiums and coverage after disasters occur. When the risks become too great, private insurers may simply leave. Something like this happened in Florida after large losses from hurricanes and windstorms. As insurance is essential for financing buildings, the state itself became an insurer of last resort, accepting exposure to multi-billions of potential losses.

7. Legal requirements such as periodic inspections may mean very little if not seriously reviewed and enforced. Requirements for condo associations to maintain reserve funds for long-term maintenance have proven largely ineffective due to loopholes and lack of enforcement. The Champlain Tower that collapsed had identified $15 million in needed repairs four years ago but had less than $1 million in reserve, and when unable to agree on the necessary special assessment, several board members quit in frustration. The state’s governor, Ron De Santis, has suggested the disaster may have been an isolated incident and so far avoided any promise of increased state oversight of high-rise buildings, although the Bar Association and other authorities have initiated reviews of the licensing and inspection system.

8. The legal system will be actively involved in deciding the consequences of climate disasters. Within a few days of the building collapse, owners of units in the Champlain Towers South condo complex filed a class-action lawsuit against the condo association for the failure to “secure and safeguard the lives and property” of the owners. Hundreds of climate change lawsuits have already been filed in the United States (most to date brought by governments against large emitters of greenhouse gases). Lawsuits may be among the greatest drivers of climate action.

As time passes and the emotional impact of the condo collapse diminishes, discussion is likely to shift toward more technical issues like enforcing inspection programs and the design of more effective flood control systems. My hope is that the families and friends of those who died in the collapse will keep the impact of their sudden loss part of the discussion. The disaster had some personal meaning for me, as my parents (both long since passed away) had been owners of a unit in a similar building just a few blocks south for several decades. This personal connection brought home the vacuous nature of many debates about climate change policy. As the author Kim Stanley Robinson recently noted:

“Parochial concerns over quarterly returns . . .fade to insignificance when you take the long view and see us teetering on the edge of causing a mass-extinction event that would hammer all future living creatures. What is the value of coral reefs? Of coastal communities? Of civilization as we know it? Or temperatures within the limits of human survivability?”

Alan Miller is a former climate change officer in the International Finance Corporation (2003–13) and climate change team leader, Global Environment Facility (1997–2003)

Subscribe to receive the updates

Recent Posts

President-elect Trump has promised to again withdraw the U.S. from the Paris Agreement.

President-elect Trump has promised to again withdraw the U.S. from the Paris Agreement.